Veronica Sahagun ( 2011). Path in the Sierra.

Veronica Sahagun ( 2011). Path in the Sierra.

The source of this (E) Motions project is a geographical region that played a key role in the history of the Conquest of Mexico. This area is known as Central Mexico and it includes the states of Veracruz, Tlaxcala, Puebla, Estado de Mexico, Distrito Federal (Mexico City) and Morelos. As mentioned in the narratives of Texcoco and Xochimilco, Mexico City used to be the capital of the Aztec empire. Central Mexico is a predominantely Nahua region. The Nahuas are one of the largest Indigenous groups of Mexico. It is also common knowledge that the Aztecs belonged to this group and that Nahuátl was their language. The legend states that they came from the north (somewhere near the estate of Nayarit), from a land called Aztlán. They were looking for a new place in which to settle. They found that place in Central Mexico. The Mexicans were expecting to find a sign that indicated where to settle. This sign was communicated to them by their God Huichilopocthli. They were looking for an eagle devouring a snake (the emblem of the Mexican flag). They found it in a small piece of land in the middle of the Texcoco lake in the Valley of Mexico. In 1325, the pilgrims founded the great Tenochtitlán, the capital of their soon to be empire[1]. López, Lujan and Levin (2006) provide a narrative of this magnificent city as seen by the first Spanish explorers:

On November 8 (of 1519), the Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés and five hunred Spanish soldiers stood in a mountain pass above Tenochtitlán and were amazed. As they came down the mountain they saw an island city of more than 200, 0000 in a shining blue lake, connected to the mainland by great causeways, wide flat roads built across the lake. Tall “towers” (as the Spaniards called the pyramids) seemed to rise from the water itself. As they came closer, they could see that the city gleamed with white stucco. Canals like those in Venice in Italy ran alongside many of the wide straight streets. Bigger, cleaner, more elegantly laid out than any European city of the time, Tenochtitlán seemed an enchantment, a city from a story book, so astonishing that some soldiers asked if it was a dream. It was the most beautiful city in the World, Cortés wrote to his king Charles I of Spain (p. 10).

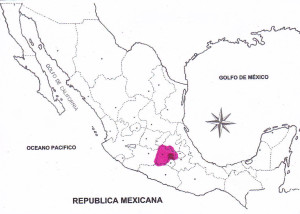

My animated collages engage with locations within the south east of Mexico City and east of the Estado de Mexico. The map on the right is widely used in primary schools of Mexico. I recall learning Mexic an geography through the coloring of the states; the association between the name of the state and the state helped me to memorize all of them. The larger pink area corresponds to the Estado de Mexico. The darker red spot is Mexico City.

an geography through the coloring of the states; the association between the name of the state and the state helped me to memorize all of them. The larger pink area corresponds to the Estado de Mexico. The darker red spot is Mexico City.

I chose to work sites located in this area because this is where I have spent most of my life. Last year, a Mexican newspaper called El Universal published a note in reference to the UN’s list of the world’s most populated cities. Mexico City, along with New York City, occupies third place with a 20.4 million population (El Universal, Sociedad, April 6, 2012). Such large population makes Mexico City a challenging place to live in and to navigate: crowded, polluted, noisy and violent. They say that New York City never sleeps. I believe this could also be applied to Mexico City. Like New Yorkers, people from the Distrito Federal are famous for being temperamental and intolerant. Even so, I consider myself to be a rural-oriented person. I am the oldest child of a middle class university-educated Mexican couple. My parents met in a small town called Texcoco, located in the Estado de Mexico in the early 1970s. At that time, both of them were students at the Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo (UACH), the prestigious agricultural university within Central Mexico. Just like many others among their generation, my parents believed that transformation of the Mexican society needed to take place by supporting communities with limited access to education, employment and technology. They remained true to this goal by integrating their professional practice into the rural world. As I now see it, they understood that the roots of Mexican identity could be found there.

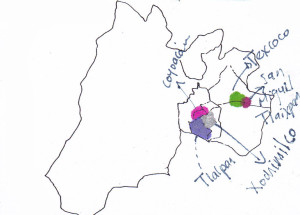

They transmitted their vision to me in several ways. My father, for example, used to take me to the cornfields. There, I saw him interact with the farmers. I learned that corn is basic to the Mexican diet, but I also learned to appreciate the work of the people who produce it. Both of my parents also taught me to appreciate handmade products created in the rural communities.  I grew up surrounded by clay pottery, handmade basketry, wooden masks and miniature sculptures, as well as handmade Indigenous textiles.As a result, public sites like plazas and market places—locations where one can acquire these rural handmade items–embody childhood and youth memories that are dear to me. My animated collages are visual narratives that represent my connection to a number of these sites. Within Mexico City, I developed pieces in response to three delegaciones (districts): Coyoacan, Tlalpan and Xochimilco. Tlalpan and Xochimilco are considered to be rural areas. The locations within the eastern area Estado de Mexico include Texcoco and San Miguel Tlaixpan.

I grew up surrounded by clay pottery, handmade basketry, wooden masks and miniature sculptures, as well as handmade Indigenous textiles.As a result, public sites like plazas and market places—locations where one can acquire these rural handmade items–embody childhood and youth memories that are dear to me. My animated collages are visual narratives that represent my connection to a number of these sites. Within Mexico City, I developed pieces in response to three delegaciones (districts): Coyoacan, Tlalpan and Xochimilco. Tlalpan and Xochimilco are considered to be rural areas. The locations within the eastern area Estado de Mexico include Texcoco and San Miguel Tlaixpan.

References

Ciudad de mexico, la tercera ciudad mas poblada del mundo: ONU. (2012, April 6). El Universal

López Luján, L., Levin, J., & MyiLibrary. (2005). Tenochtitlán. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

[1] I am providing a summarized version of the legend. This is what Mexican children are taught in primary school. I learned it by heart in second grade. For further details on this legend, refer to Mexico before Cortez: art, history, legend by Ignacio Bernal; translation by Willis Barnstone; with additional English-language material by Ignacio Bernal.